● Next Meeting Status:

Cancelled

● Host Society for the

BANS 2011 Congress

held in Southport

Ballindalloch Works Notes -

Paper Money of the Industrial Revolution

Eric C Hodge

Merchant countermarks on Spanish colonial dollars are known from a number of industrial concerns in the early years of the nineteenth century and, though rare, have been studied and written about for a number of years. Much less well known are the very rare issues of paper money. OWLNS member Eric Hodge presents here an account of the notes issued from the Ballindalloch Cotton Works, a business which had previously issued countermarked dollars.

Paper money has always seemed to me to have a fairly basic control feature. As a note is produced, it is sequentially numbered, one after the other. In the case of Ballindalloch Works, however, this does not appear to be the case and perhaps more research is required to understand their method of control.

The reason for this article is to list the known notes, or checks as they are referred to, and from the available examples (Table 1), make some attempt at understanding the reasons for their issue and the use of such an apparently unusual numbering system.

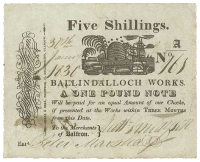

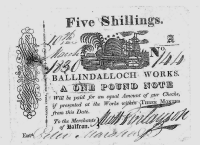

Ballindalloch Works issued two types of notes. One is designated Five Shillings with the text ‘A One Pound Note Will be paid for an equal Amount of our Checks, if presented at the Works within Three Months from this Date. To the Merchants of Balfron.’ (Fig 1)

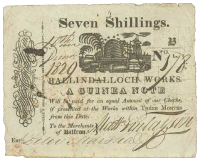

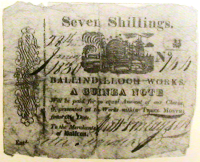

The other is for Seven Shillings with the text ‘A Guinea Note Will be paid for an equal Amount of our Checks, if presented at the Works within Three Months from this Date. To the Merchants of Balfron.’ (Fig. 2)

To see the notes in greater detail, hover your cursor over each of the small images in turn

Fig 1

Fig 2

Both notes (Figs. 1 & 2) are signed by Matt. Finlayson and Peter Marshall and, according

to Symes¹: “they have the two principal security devices of the period -

The position of Peter Marshall at the Works is not known. He was probably the accountant,

or accounts officer, as his signature is next to ‘Entḏ.’ presumably meaning the note

details had been recorded in the Books of Account before issue. Matthew Finlayson

was the manager of the Ballindalloch Cotton Works owned by James Finlay & Co. -

Andrew Macmillan, whose Scottish banknotes were sold in Spink 5027 on 12th September 2005, passed on to me his records of Ballindalloch notes. This was the foundation of Table 1, that lists six Five Shillings notes, all prefixed A and numbered from 106 to 164, and fourteen Seven Shillings notes, all prefixed B and numbered 103 to 194.

Table 1 Ballindallloch 5/-

Notes shown in serial number order, by value

VALUE

NUMBER

YEAR

DATED

WEEK

From Table 1 I have created Tables 2 and 3, below, which show I have obtained photos for all examples except two Seven Shillings notes, B126 and B149, both of which were listed in the same CNG auction, with similar dates to other notes in Table 1 above e.g. B130 and A134 respectively.

In Manville², page 16, it is stated that wages were paid weekly, generally on Thursdays. As can be seen from Table 1, the note dates are not always a Thursday. This could be because the notes were made out when accounting staff were available, but paid out on Thursdays, or it could indicate that the notes were used for a variety of reasons, such as paying local Balfron merchants for supplies to the Works, as well as being used for wages.

‘Obviously the notes had to be acceptable to those receiving them, so presumably they did not fear that the works were in any financial difficulty. Lack of silver coin seems the likely reason for their issue.’ (Macmillan)

It is certainly interesting that the notes state ‘To the Merchants of Balfron.’ leaving

us in no doubt that the notes were expected to be spent in the village of Balfron

and not in any ‘work’s-

VALUE

NUMBER

YEAR

DATED

VALUE

NUMBER

YEAR

DATED

Table 2 Ballindallloch 5/-

Notes shown in Issue Date order

Table 3 Ballindallloch 5/-

Notes shown in Serial Number order

In Table 2, I have listed the notes in issue date order ignoring the different values.

The period spans from 16 September 1829 to 30 March 1830, approximately seven months.

The issue dates do not seem to bear any relationship to the note values as the five-

In Table 3, I have sorted the notes into serial number order leaving out the prefix A for Five Shillings and B for Seven Shillings notes. It can be seen from the illustrations, Figs. 1 & 2, that only the number was hand written, so it seems logical that notes were numbered as issued without any differentiation for value. The most salient point here is the duplication of number 144.

Our sample of notes is only twenty, listed in Tables 2 & 3, so we must bear in mind that any conclusions are conjectural. If we take the period of issue as seven months then this is a fairly short time span and must reflect a type of emergency issue.

This was a period of British silver-

Why, therefore, did the Ballindalloch Cotton Works need to issue these notes?

Is it possible that the business was temporarily embarrassed for a lack of coin due to adverse trading conditions, and the notes were a means of avoiding more difficult decisions such as increasing borrowings or laying off workers? In fact in Manville², mention is made that the original business (pre Finlay) went bankrupt in 1794 and the owner, Dunmore, in 1800. The reason seems to have been too much reliance on the water supply to drive the mill. The supply was not constant and coal to operate steam machinery was found to be too expensive to bring to the mill.

‘By mid-

Whatever the reason for their issue, the Ballindalloch notes do appear to be a stop-

If notes were dated and issued (we must assume if they are dated they would have been issued) in strict numerical sequence, Tables 2 and 3 should reflect the same order of detail. This is not the case so we must speculate as to the reasons.

The notes were issued for payment ‘within Three Months from this Date.’ One can therefore

presume that when the three months were up, the note number could be used again.

When a note had been presented for payment, it could not be re-

To see the notes in greater detail, hover your cursor over each of the small images in turn

Fig 3

Fig 4

It would appear that note numbers could be re-

We have no detailed provenance for the notes in Table 1. There are not many notes

known, but Jonathan Callaway, a bank note expert, in private correspondence, asked

‘why have so many of these notes survived, all fully signed and issued…Other non-

Part of the answer to that query could be the retention of the notes at the Works,

after presentation, and then the re-

Another reasonable assumption is that Table 1 is made up of notes from many different sources over the years and is therefore a good cross section of the notes issued for the seven months, as only the month of October 1829 is missing.

So the question now is why are all the notes numbered between 100 and 200? Could

it be possible that numbering commenced at 100 and very few numbers were issued because

most notes were returned to the Works very quickly and the numbers re-

The earliest dated note, 16 September 1829, is numbered 153 (Fig. 2, and Table 2).

This should mean that there were at least 53 notes, assuming the numbering started

at 100, issued before this one, and all dated 16 September 1829 or before. We in

fact have fourteen notes (Table 3) numbered before 153, but all dated later than

16 September 1829. I believe this is highly significant in supporting the number

re-

Another clear indication for re-

A method for issuing and recording these notes, put forward by Macmillan, is that

‘the numbers might correspond with pages in a ledger -

Why would the Works want to re-

A further idea for this unusual date and number sequencing could have been some sort of ‘privy mark’ or secret linking of date to number to prevent forgery. This is possible, but normal numbering and proper recording in the Books of Account should have given adequate control.

So if the Ballindalloch Cotton Works were experiencing short term liquidity problems

at this time, then the issue of notes could have alleviated the problem and the re-

Perhaps, therefore, we should never take too much for granted, questioning even the most basic numbering system!

References & Requests

¹ Symes, Peter. The Ballindalloch Note Issue of 1830.

The International Bank Note Society Journal, volume 36, No. 4, 1997, (revised 2003).

² Manville, H.E. Tokens of the Industrial Revolution -

Spink, London, 2001, pp. 15-

BNS Special Publication No. 3

Winner of the 2002 book prize of the International Association of Professional Numismatists.

The Author would welcome any information regarding known notes not included in this survey. He may be contacted using the OWLNS Message page. Click on the quill, and the appropriate page will open.

Send Us A Message

Where to next?

This paper was written in

November 2010