● Next Meeting Status:

Cancelled

● Host Society for the

BANS 2011 Congress

held in Southport

The Buffalo Nickel

A Modern Classic?

It isn’t often that I can find anything praiseworthy to say about modern American culture but I’ve had to grudgingly admit to admiring certain twentieth century currency coin issues. It’s even harder to state that, in my opinion, some American coins are superior in both design and manufacture to our own contemporary issues. I deliberately pinpoint the words design and manufacture as one often lets the other down in the resulting coin.

Of all the twentieth century American designs one, in particular, not only captures

the character of the West and is ‘All American’ in its iconography but is a yardstick

for good coin design and production. I refer not to a commemorative issue or short-

The coin’s story is well documented and, as a collectors’ piece, even warrants its own national collectors’ club with thousands of members. Not bad for a coin which was only issued between 1913 and 1938 – and even then not in all years. Apart from minor modifications even the design remained immobilised for 25 years. So what is the appeal, what is all the affection and fuss about? Well, simply, quality endures.

I’ll start at the beginning -

During his presidency of the United States, Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt had often

voiced his contempt for the rather lack-

After a number of essays were submitted, one by James Earle Fraser, a former assistant

to the sculptor Augustus Saint-

Prominent on the obverse was a profile ‘Indian’ head with the date and the word LIBERTY.

Indians had been portrayed before on American coins, but they were always shown as

Caucasian white men wearing an Indian head-

In keeping with the strictly American theme, he depicted an American bison on the reverse. The inscriptions UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and E PLURIBUS UNUM are placed over the bison (or ‘Buffalo’) with the denomination FIVE CENTS in the exergue. To Fraser the buffalo symbolised the ‘Winning of the West’ and provided a perfect unity of theme with the native American on the other side.

The design was hugely popular with the public, although there was the expected criticism from certain quarters, as with any new design. Over 1.2 billion ‘Buffalo’ nickels were minted from 1913 to 1938 at three mints: Philadelphia (no mintmark), San Francisco (a small ‘S’) and Denver (a small ‘D’).

Hover your cursor to

see the coins in detail

Buffalo Nickel 1935

Philadelphia Mint

The mintmark is on the reverse under the denomination and the designer’s initial is shown as a small incuse ‘F’ below the date.

Mintmark ‘D’ in exergue of 1938 Denver nickel

Designer’s Initial ‘F’

below date on obverse

Now, having described the piece, what of interest can be said about this coin? The answer, surprisingly, is quite a lot. Taking the obverse first, this was modelled using the combined features of three real Indian chiefs: John Big Tree, an Iroquois; Iron Tail, a Teton Sioux, and Two Moons, a Cheyenne.

John Big Tree was probably the best known of the trio as he was later hired by the Falstaff Brewing Company to tour the country as the ‘Indian on the nickel’ and thus promote their products. Two Moons had been a Cheyenne Chief at the Battle of Little Big Horn and had even taken part in the resulting massacre of Colonel Custer’s troops, just 40 years before. He visited Washington, D.C. several times, even meeting President Woodrow Wilson. Two Moons was in his sixties when Fraser used him as a model for the Indian Head. The new coin spread Two Moons' fame, but it didn't bring him any royalties. He died in 1917, just four years after the Buffalo nickel made its debut in 1913. As for Iron Tail, not much is known, and he seems to have slipped from the pages of history.

Fraser said that his goal had been to create a "truly American" coin; when the first Buffalo nickels were released in February 1913, they certainly had everyone talking. A coin collectors' magazine described the Native American portrait as “a work of art, powerfully modelled and strong." Treasury officials were quick to point out that it was a composite portrait, which wasn't supposed to represent any particular Indian. Coins from the first bag to go into circulation were presented to outgoing President Taft and no less than 33 Indian Chiefs at the groundbreaking ceremonies for the National Memorial to The North American Indian at Fort Wadsworth, New York.

Now, what can be said about the reverse design?

Technically, the ‘buffalo’ is not a buffalo at all, but a North American Bison; buffaloes

are found mostly in India and Africa – but not in the United States. The miss-

The buffalo used as a model for the reverse of the nickel was almost as famous as

the Indian Chiefs. Far from being a wild Plains Buffalo he was, in fact, a long term

resident of the Bronx Zoo, given the name ‘Black Diamond’ because of his unusually

dark coat. Not everyone was impressed with Fraser’s portrayal of the buffalo. The

director of the Bronx Zoo called the bison on the nickel a “…sad failure with its

head drooped as if it had lost all hope in the world.” Despite Black Diamond’s new-

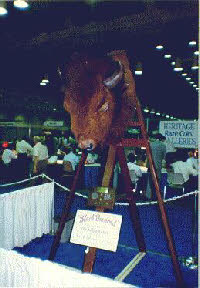

However, Black Diamond’s head was salvaged, preserved and mounted and to this day is sometimes exhibited at various coin shows and conventions across the United States.

As with most coin types there are numerous varieties, mint errors and minor modifications which appeal to the observer of minutiae, with his 20x glass and notebook tucked in his anorak, thus creating quite a cult following for the coin!

The most well known of these varieties and one which commands a hefty premium is

the famous ‘three-

There are of course other varieties: overdates, double-

All this does at least show that, comparing it with the earlier and bolder British

designs, our ex-

And, as an afterthought, there are two additional items of interest. American ‘nickels’

are actually made of cupro-

Alan M Dawson

Buffalo Nickel 1937

Denver Mint Missing Leg

Where to next?